Cooperation (Angelika Thäle)

suggested citation: Thäle, A. (2022). Cooperation. In J. Frohn (Ed.), Inclusive Teaching and Learning - Glossary. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. URL: https://hu.berlin/fdqi-en-glossary.

► Download the PDF to this glossary entry

The pedagogical discourse on inclusion pays particular attention to the many forms of cooperation1 at school and in the classroom: cooperation between pupils, between pupils and teachers, between educators, with educational facilities outside of school, or with parents.

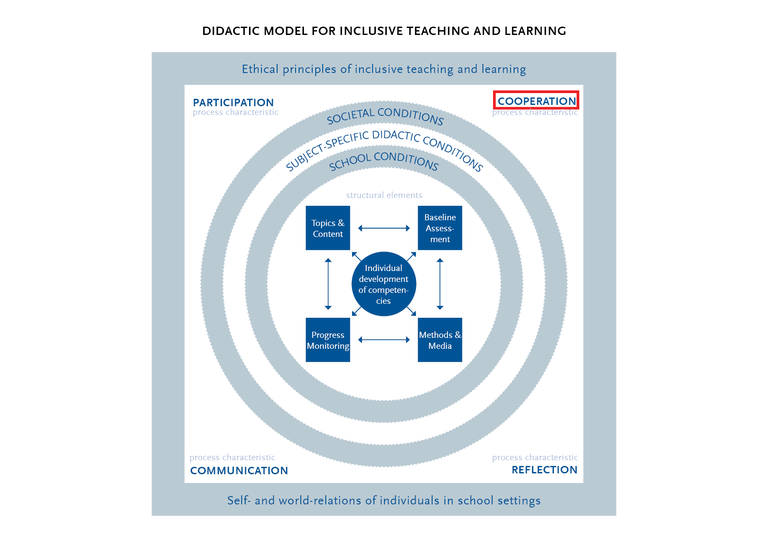

Cooperation is one of the four process characteristics in the Didactic Model for Inclusive Teaching and Learning, alongside participation, communication and reflection. This article focuses on cooperation between pupils and cooperation between teachers.

Cooperative learning is understood as a core element of inclusive practices (cf. Boban & Hinz, 2008, p. 74). This refers to cooperation between pupils – with their different competencies – on a common learning object. It is assumed that highly heterogeneous learning groups offer a particular incentive and a great opportunity for co-constructive learning processes2. However, there is currently very little empirical research into the ‘degree’ to which heterogeneity (of performance) in partner and group work is actually beneficial to the learning of individual pupils. This appears to vary depending on the learning content and the competencies being developed. When developing reading fluency using the partner reading strategy, for example, the most successful partnerships have proven to be those in which the levels of reading attainment do not diverge too greatly (cf. Rosebrock et al. 2016, pp. 103f.).

Johnson and Johnson (2008) identified five basic elements in connection with cooperative learning in inclusive environments: positive interdependency, individual responsibility, direct interaction, training social competencies and group reflection (cf. Avci-Werning & Lanphen, 2013, pp. 151ff.).

Cooperative work on a common object (cf. Feuser, 2013) is a central concept in the developmental logical didactics of Georg Feuser, who made a groundbreaking contribution to integrative and inclusive didactics. Cooperation is viewed as a developmental necessity, defined as the functionally divided coordination of individual activities with the aim of attaining a common goal (cf. ibid, p. 287). Feuser states that in terms of teaching methodology, this form of cooperation can be best realised in project work, so that the common object is not bound to one subject. The critical objection can be raised that pupils do not inevitably benefit from cooperative learning opportunities, as they require a high degree of independence in planning and execution (cf. Walter et al. 2012, p. 450).

Wocken’s description of common learning situations corrects and expands upon the strenuous demands on pupil cooperation formulated by Feuser (Wocken, 1998). As well as cooperative learning situations (as understood by Feuser), he also mentions communicative, co-existent and subsidiary situations (cf. Wocken, 1998). Particularly with regard to subsidiary learning situations (supportive or prosocial learning situations), helping processes are not one-sided; all children and adolescents can also experience themselves as helpers (cf. Zimpel, 2014, p. 22).

One of the central resources and challenges of inclusive teaching is pedagogical cooperation between teachers. The two-teacher system has been a principle of integrative/inclusive teaching since the first attempts to create integrative schools (cf. Feuser & Meyer, 1987; Wocken, 1988). The allocation of resources is the subject of regular discussion, particularly when pupils who need high levels of support (such as those with significant physical or cognitive impairments) learn together in the same class.

Moreover, the importance of multi-professional cooperation is emphasised at both teaching and institutional levels. This includes cooperation with staff at other educational, therapeutic or social facilities, and various forms of teamwork at the different structural levels of the individual school (such as the year team, the governors, the subject committee or school council).

With regard to actual cooperation during lessons, a distinction can be made between different methodological/didactical approaches, such as team teaching, parallel teaching and teaching differentiated by station or standard. Team teaching is understood to be a qualitatively valuable form of group teaching, distinct from other approaches involving the (partial) division of the learning group (cf. Lütje-Klose & Willenbring, 1999, p. 16). In many cases, a work method has become established in inclusive (subject) teaching practice that entails a division of functions and is clearly reflected in a distribution of roles (lesson planning and teaching support). While elementary or subject teachers have the greatest responsibility in the classroom, special needs teachers or educators often play a supporting role (cf. Kreis et al. 2014). This distribution of roles always introduces a certain hierarchical structure into the work organization of a teaching team (cf. Wocken, 1988, p. 230). This can be balanced; for example, by changing roles at specific points during the lessons or between subjects.

References

Avci-Werning, M. & Lanphen, J. (2013). Inklusion und kooperatives Lernen [Inclusion and cooperative learning]. In R. Werning & A.-K. Arndt (Ed.), Inklusion. Kooperation und Unterricht entwickeln [Inclusion. Developing cooperation and teaching] (p. 150–175). Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Boban, I. & Hinz, A. (2008). »The inclusive classroom« - Didaktik im Spannungsfeld von Lernprozesssteuerung und Freiheitsberaubung [»The inclusive classroom« - Didactics in the area of tension of learning process control and deprivation of liberty]. In K. Ziemen (Ed.), Reflexive Didaktik. Annäherungen an eine Schule für alle [Reflexive Didactics. Approaches for a school for all] (p. 71–98). Oberhausen: ATHENA-Verlag.

Feuser, G. (2013). Die „Kooperation am Gemeinsamen Gegenstand“ - eine Entwicklung induzierendes Lernen [The „cooperation on the common object“ - a development of induced learning]. In G. Feuser, J. Kutscher, W. Jantzen, I. Beck & P. Wachtel (Ed.), Entwicklung und Lernen [Development and learning] (p. 282–293). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Feuser, G. & Meyer, H. (1987). Integrativer Unterricht in der Grundschule. Ein Zwischenbericht; Zwischenbericht zum Stand und Fortgang des Schulversuchs Integration (II) an der Grundschule Robinsbaljen Bremen-Huchting [Integrative teaching in primary schools. Interim report; Interim report on the status and progress of the school pilot project Integration (II) at the primary school Robinsbaljen Bremen-Huchting] (March 1986). Solms-Oberbiel: Jarick Oberbiel.

Johnson, D. W. & Johnson, R. T. (2008). Wie kooperatives Lernen funktioniert. Über das enge Verhältnis scheinbar widersprüchlicher Ansätze [How cooperative learning works. About the close relationship of seemingly contradictory approaches]. In C. Biermann, M. Fink, M. Hänze, D. H. Heckt, M. A. Meyer & L. Stäudel (Ed.), Individuell lernen - kooperativ arbeiten. Friedrich Jahresheft XXVI 2008 [Individual learning - cooperative working] (p. 16–20). Seelze: Friedrich Verlag.

Kraif, U. (Ed.) (2007). Duden – das große Fremdwörterbuch. Herkunft und Bedeutung der Fremdwörter [Duden - the great dictionary of foreign words. Origin and meaning of foreign words] (4th ed.). Mannheim: Dudenverlag.

Kreis, A., Wick, J. & Kosorok Labhart, C. (2014). Wahrgenommene Zuständigkeiten von pädagogischem Personal in integrativen Schulen des Kantons Thurgau [Perceived responsibilities of pedagogical employees in integrative schools in Canton of Thurgau]. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 6 (4), 333–349.

Lütje-Klose, B. & Willenbring, M. (1999). „Kooperation fällt nicht vom Himmel“ - Möglichkeiten der Unterstützung kooperativer Prozesse in Teams von Regelschullehrerin und Sonderpädagogin aus systemischer Sicht [„Cooperation does not appear from nowhere“ - Possibilities to support cooperative processes in teams of regular school teacher and special education teacher from a systematic perspective]. Behindertenpädagogik 38 (1), 2–31.

Martschinke, S. (2015). Facetten adaptiven Unterrichts aus der Sicht der Unterrichtsforschung [Facets of adaptive teaching from the perspective of classroom reseach]. In K. Liebers, B. Landwehr, A. Marquardt & K. Schlotter (Ed.), Lernprozessbegleitung und adaptives Lernen in der Grundschule: Forschungsbezogene Beiträge [Learning process support and adaptive teaching in primary schools. Research-related contributions] (p. 15–32). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Rosebrock, C., Nix, D., Rieckmann, C. & Gold, A. (2016). Leseflüssigkeit fördern. Lautleseverfahren für die Primar- und Sekundarstufe [Advancing reading fluency. Phonetic reading methods for primary and secondary schools] (Praxis Deutsch, 4th ed.). Seelze: Klett Kallmeyer.

Walter, J., Ide, S. & Petersen, A. (2012). Kooperatives Lernen auf der Basis von Lesetandems. Entwicklung und Evaluation eines tutoriellen Lesetrainings zur Steigerung der Leseflüssigkeit [Cooperative learning on the basis of reading tandems. Development and evaluation of a tutorial reading training to progress reading fluency]. Zeitschrift für Heilpädagogik 63 (11), 448–464.

Wocken, H. (1988). Kooperation von Pädagogen in integrativen Grundschulen [Cooperation of educators in integrative primary schools]. In H. Wocken, G. Antor & A. Hinz (Ed.), Integrationsklassen in Hamburger Grundschulen. Bilanz eines Modellversuchs [Integrated classes in Hamburg primary schools. Balance of a pilot project] (p. 199–274). Hamburg: Curio-Verlag Erziehung und Wissenschaft.

Wocken, H. (1998). Gemeinsame Lernsituationen. Eine Skizze des gemeinsamen Unterrichts [Common learning situations. An outline of common teaching]. In A. Hildeschmidt & I. Schnell (Ed.), Integrationspädagogik. Auf dem Weg zu einer Schule für alle [Inclusive education. On the path for a school for all] (p. 37–52). Weinheim; München: Juventa.

Zimpel, A. F. (2014). Einander helfen. Der Weg zur inklusiven Lernkultur [Helping each other. The path to an inclusive learning culture] (2nd ed.). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

[1] In etymological terms, the word ‘cooperation’ is derived from the Latin verb ‘cooperari’ (‘to work with’, Kraif DUDEN, 2007, p. 763) and can simply be understood as ‘working with others’.

[2] In the context of learning and teaching, ‘co-construction’ means that pupils rethink and organise their personal knowledge through social dialogue, consequently diversifying their competencies and understanding to build a body of individualised knowledge (cf. Martschinke, 2015, p. 19).